1 / 22

1 / 22

1 / 22

1 / 22

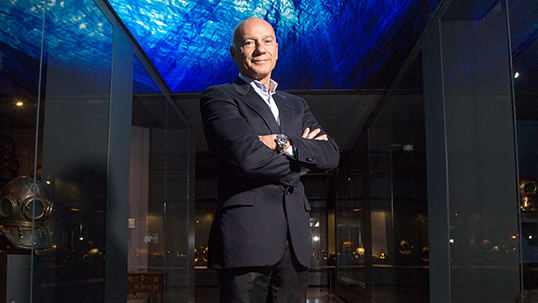

Born in Büyükada, Jeff Hakko is a sea enthusiast who developed a curiosity for the underwater world at the age of 6-7 and became a ‘master’ after receiving professional diving courses during his years at the university. The diving helmet he saw in 1990 in France while attending an underwater symposium changed his entire life. And in 2018, he donated the Historical Diving Equipment Collection he built in nearly 28 years to the Naval Museum in Beşiktaş, Istanbul. We talked with Jeff Hakko about his extraordinary collection referred to as one of the world’s three most special Historical Diving Equipment Collections and his passion for the underwater world.

You were born in Büyükada. How did Büyükada affect your current lifestyle and areas of interest?

Everything started there. Of course, back in those days, Büyükada was not as it is today; there were much less people. The sea was indigo blue, the water was so limpid that you were able to read the title of a newspaper lying 7-8 meters deep underwater. When I was 6-7 years old; I used to get in the water and not come out. I was scolded by my mother while my lips turned purple and my fingers puckered. I was always in the water, my head was always under the water but I could not see anything clearly. I could dive for as long as my breath allowed me to, and then I had to come out. Our brothers at the Anatolian Club had masks, flippers on their feet and rifles in their hands. “I want one set of these too”, I insisted. Of course, my father did not listen to me that much for I was still a little child. Some time went by, I turned 9 and I bought flippers and a snorkel from the pharmacy at the Büyükada Clock Tower Square with my first pocket money, which was the real breaking point. Now I was able to see under the water. I dove as deep as I could and this way I began to explore the underwater world. When I turned 13, I also began to take a boat out and dive around the islands. This was where and how my entire story began.

You received your first diving license in your 20s.

Yes, I used to skin dive during my years as a student in the UK, but I did so with my own knowledge and resources. I could not dive anywhere I wanted to for I was required to have a license. The only solution was to take a license by completing a training program on the theory and practice of diving at an official institution. I applied to a club in the UK and received the required education. You are able to dive anywhere in the world as you please with the first badge that you receive from a prestigious club. Evidently, it does not end there, the training continues with 1 star, 2 stars, 3 stars and so forth.

You became a ‘master’ in five years...

Yes; it actually progressed naturally. I have currently suspended the education part since I have no time for it.

Do you still dive as actively as you used to?

I do even more than I used to.

Are there any particular regions in Turkey or in the world that you prefer for diving?

I absolutely recommend diving abroad. Of course, you have to plan it very carefully. The amount of time you are able to dedicate to it is important, as it is hard for a businessperson like me to go to Australia for two weeks. You need to be able to access your diving location of choice easily. Considering all these, the Maldives are quite accessible; you get there in 7 hours. You arrive there in the morning after a night flight. Sharm el Sheikh, so the Red Sea and the Maldives are two very important destinations for diving and the underwater world. The underwater in the Red Sea is still very beautiful but it has become highly commercialized. There is another serious problem in the Maldives. Unfortunately, this affects all of us and will do even more so in the future. Because of global warming, 60 percent of the corals are already dead. A coral crumbles after it dies, so when you dive in the Maldives, you see the ocean floor covered in grey sticks that are completely broken, it is truly heartbreaking. Thankfully, the fish are still safe, wandering around with their colors and magnificence and 40 percent of the corals have color. It is also very pleasant to dive in the Far East around various Indonesian islands.

Do you plan your vacations completely around diving?

Yes. I take long weekend vacations during the summer and I generally prefer to stay in Turkey. On the other hand, for vacations taking place in other months, I prefer to go abroad with diving as a constant priority.

Any diving centers you particularly enjoy in Turkey?

In Turkey, Kaş is definitely the best place for diving. The waters are very limpid and the beauties waiting for us deep down are outstanding. Everything from a submerged aircraft to a cave. Plenty of species of fish. But it is relatively harder to reach Kaş. This in fact is an advantage; it is also why there are relatively fewer divers in Kaş. When you go there, you have to dive with a diving club; you cannot act on your own, as you please. If you are going there with a departure from Bodrum, then it is different. As I own a boat designed specifically for diving, it is much more practical for me to dive in Gökova during the weekends. Gökova is one of Turkey’s largest gulfs, with several diving points. It is relatively clean for the moment but it is being polluted at a very high pace, unfortunately. I also enjoy diving at the Bozburun Peninsula.

How was the most dangerous diving experience you have ever had?

The golden rule of diving is to never dive alone; you always have to have a buddy. We were at a diving session with a club in Southern France. If you are diving with a club, they match you with a buddy in line with your level of experience. So, they matched me with this Dutch diver as we had the same badge level. We dove, and at 25 meters, my air supply stopped working. This is the worst thing that can happen to a diver. 25 meters of depth is not huge but it is still quite a lot. Training and experience are crucial here. You may get drown if you panic, but if you remain calm and signal the problem to your buddy and ask for help, you two can safely go back to the surface by buddy-breathing (sharing the air). Thus, I gave him the signal, and he extended his spare regulator to me as he was also highly experienced, and we rose back to the surface together. There, I checked my air again and everything seemed to be normal. Yet the same problem occurred as we dove back to 25 meters. We said “this dive is over” and returned to the boat. I told them, “there is a problem with the regulator, please take care of it”. They said, “OK, we will do so when we debark”. There are 10-12 divers on the boat, and all the equipment is stored in the same place after the dive is over. It would not be possible for them to figure out which regulator was broken if I put it in the same place with the other materials. It could be very dangerous if that equipment ended up in the hands of a less experienced diver, he or she may be unable to react the same way and drown. I had to take a definitive precaution, so I cut the regulator’s hose with a knife. I said, “I am sorry, I will compensate you for the damages, but this way the regulator will not get mixed”. Since then, I do not use the equipment if it is not brand-new or I take my own equipment with me instead.

Do you have a diving story that you have particularly enjoyed and found exciting?

I cannot forget the first time I dove in the Red Sea to a British merchant ship that sank during WWII. There was an extreme water current, you descended holding a rope attached to the back of the ship and as you did so, your body stood in a horizontal position because of the current’s strength. You entered the ship and the current suddenly stopped, and you found yourself in a gigantic cargo vessel. Motorcycles, tanks on the upper deck and they all had been lying there since WWII. Can you believe that? And algae, corals and fish surrounding them... A moray eel coming out of the tank’s barrel. An unforgettable, surreal experience.

Did you start taking photographs to document the beauty of the underwater world?

I took some beautiful pictures as years went by, but I have never had an extreme enthusiasm for documentation. Photography is another branch, a different ambition and discipline. To take pictures takes time and concentration, but I prefer to hear my own breathing, to feel what is going on around me and to be fully in the deep blue when I dive. I have very dear friends taking great pictures, and I leave that task to them.

What does diving mean to you, in one sentence?

Deep blue therapy...

Now I would like to talk about your collection. You started to work on your Historical Diving Equipment Collection in 1990. What was the first item in it?

At an underwater symposium I attended in 1990 in Southern France, I saw a shiny, American Mark V type diving helmet exhibited on a booth; it almost cast its spell on me and I instantly forgot about the symposium and all. I went back in time; I thought about the diver who used it. Under what conditions and where was he using it? What else did he wear? That was another breaking point in my life. I continued attending the symposium, but always with this helmet in mind. Two days later, I stood before it once more on my way out. Then I spotted a small tag behind the booth saying “this diving helmet has been leased by this person”. I noted down his phone number. On my way back to Istanbul, I bought a divers’ magazine at the Nice Airport. The same person’s ad was in that very magazine. I called him from Istanbul. He was Christophe Facon, a gentleman living near the French city of Brest. I said, “I saw this helmet of yours and I loved it; is it for sale?”. He said it was, and that he had other helmets in his portfolio as well. “Can you send me their pictures”, I asked, and he said, “these things do not work well with pictures, so come here if you want to see them”. Two days later, I found myself in Brest, and I stayed there for two days although I intended to do so just for one day. He hosted me at his house, we had a great time and the magic continued with all these stories he kept telling me... The materials I saw there and that helmet marked the beginning of my collection.

How many helmets did you acquire from this gentleman?

Only that helmet, but as far as I can remember, I also bought two pairs of shoes, a knife and probably a compass.

Then did you add other diving helmets, shoes, knives and compasses to your collection?

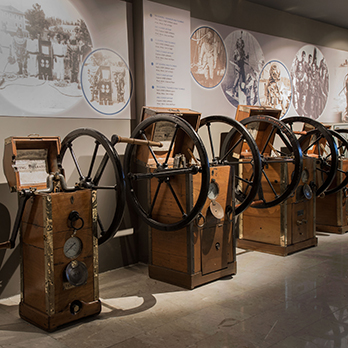

To be able to dive in the past, you needed a fully equipped diving suit we call the ‘standard uniform’. For instance, they used pumps, hoses and other materials to be able to supply the divers with air. I came to realize that these diving materials were so rare and valuable... I suddenly began to think as if I had a limited amount of time and I had to collect them. Unfortunately, these objects had been melted by ignorant hands in the past for their value in copper and brass; a massacre took place. The surviving objects, on the other hand, were very limited in number, very expensive and you usually came across them at auctions. This is why I came up with a plan. “I live in Turkey”, I thought, “so I have to have all the materials available in Turkey before they disappear”. I began to conduct a very detailed research so that they did not go anywhere, they remained in safe hands and they did not end up in a junk store. In a country like Turkey surrounded by the seas on three sides, people dive for work, for making a living, for sponge fishing. This meant that this material had to be available in Turkey. Starting in 1990, I hit the road to find these objects and continued to do so for years. I went everywhere, from Istanbul to Rize, from Izmir to Iskenderun. In Iskenderun, I came across the first helmet that I bought from Turkey.

Whom did you buy it from ?

From a diver named Süleyman (Sülo). He is still alive and active. He even called me the other day and we chatted. This has another great aspect; you stay in touch with the people you buy these helmets from and they know you. Whenever an item emerges or a different item makes an appearance, its picture comes to you. This is why all divers in Turkey know me, and even if they do not intend to give me the item that they have found, they send me its picture. “Brother Jeff, what is this, what year is it from, what is its provenance?”, they ask me.

What is the chronological scope of your collection?

The period in which the historical diving materials were produced is well established, so these objects belong to the 1829-1950 period. After that, the scuba begins.

Looking at the history of the diver’s suits, why is the underwater suit for one person designed by John Lethbridge in 1715 considered important?

What Lethbridge built was an experimental barrel produced for diving. One person enters it and extends his arms out of it from both sides. These are nowhere to be found in any museum in the entire world. The first diving helmet, on the other hand, was a revised version of the firefighter’s helmet produced in 1829. It was designed to prevent the smoke from affecting the firefighters. Its development took nearly a decade, and they were actively used until the 1950s during which the scuba was invented.

So the diving helmets have a history of 120 years...

These remained obsolete after the scuba was born. A diver wearing the historical equipment depends on the air coming from a pump on the surface, and can only go as far and deep as the hose connecting him to the pump allows him to. You are able to go anywhere you want with the scuba for as long as the air in your tube permits.

These diving materials are so rare and valuable... Once I saw the diving helmets, I began to think as if I had a limited amount of time and I had to collect them.

Is there an item in the collection with a special place for you?

The helmet of the last diver at the Port of Marseille who worked using a helmet has a special place in the collection.

Can you describe the process leading to the donation of your collection to the Naval Museum?

The process began in 2009 with the exhibition I organized at the Naval Museum. During the event that lasted for six months, I was deeply moved by the things the visitors wrote on the exhibition notebook... They were asking “why have not we seen this collection before, where can we see it after the exhibition is over?”.

We have a club for collectors, the ‘Collection Club’, of which I am also a member. Like many of my friends at the club, I used to think “what is going to happen to our collections after us”, and I would call it a nightmare. Of course, some collections like posting stamps are easier to keep and some family members are able to take care of them. In my case, no one else was interested and they could not even understand why I was doing it in the first place. So what am I going to do? It is actually very simple. You can sell the collection but you cannot sell it as a whole; there is no one else who can attribute such a value to it. And if you divide it, the collection is dissolved, and your life’s work goes to waste. So, the best option is a museum.

I was either going to establish a museum, for which I had already made considerable effort but to no avail. Or I was going to donate my collection to a museum that would take care of it in the best way possible. I have always had close relations with the Naval Forces, and as an underwater specialist, I also collaborated with the Naval Forces Command on several occasions. Thus, I made the offer to them.

This is how the process started.

A meeting was organized in Ankara so that I could present my idea of donation to the Commander of the Naval Forces at the time. I went to Ankara, but that was actually a very sad day for me. Once I got off the plane, I found out that my very dear friend and diving partner Mustafa Koç had passed away.

The donation process for my collection began in January 2016. The physical space dedicated to the collection was designated, and the construction work for the showcases began, which was very important for the exhibition. And in June 2018, the permanent exhibition of the Historical Diving Equipment Collection at the Naval Museum was open.

Your collection is very high-quality. Some researchers refer to it as one of the three best collections of its kind in the world.

I do not (laughs).

Did you meet other collectors along the way? How is your communication with them?

You cannot help but meet the other collectors while the collection comes into existence, for a sweet competition emerges between you; but the most important aspect of it is the sharing of knowledge. You say, “I have this and you have that, so what can we do?”; you navigate from subject to subject, history steps in, you talk about various materials and sizes. This is why I know the leading collectors around the world, and I have direct personal acquaintance with at least three of them. One of them is in the USA, because he also has helmets used in the modern ages and made of alternative materials (plastic, kevlar) other than copper and brass. I limited my scope to the period 1829-1950.

Donating the collection to the museum generated a very large empty space in the house and a feeling of loneliness in me; I felt a kind of void. My amphora collection was originally at the house in Bodrum; but once this feeling of loneliness came about, I had it transferred to Istanbul.

Any decisions you regret looking back at your history of collecting?

When I was a beginner, I used to polish the objects that I found. Then I said, “I am destroying the history here”, for this helmet needs to remain as it is so that it can continue to reflect the history it represents. This went on for 4-5 years and then I stopped polishing.

I know that you have a special interest in the underwater archaeology as well as an amphora collection. Does it continue to expand? Where is it at the moment?

Yes, it does; I keep it at home. There goes the Historical Diving Equipment, here comes the Amphora (laughs).

Do you still have diving equipment at home?

Very few items which I will donate to the Bodrum Naval Museum.

Is your amphora collection your new subject of focus?

This collection was covering a large area in the house. The donation generated a very large empty space and a feeling of loneliness in me. My amphora collection was originally at the house in Bodrum. Once the necessary permits were taken, it was transferred to Istanbul. I continue with it here.

Is there a point you want to reach regarding your Amphora collection?

There is no end. One of the world’s biggest amphora collectors is a dear friend of mine. He currently owns 950 amphorae. We shall not forget that during ancient times, the amphora was the most important object used for transportation. This is why it is an infinitely rich subject matter.

Are you planning to exhibit your Amphora collection?

No, I do not want to (laughs).

Would you want to in the future?

I will probably donate them somehow and some day, when I will be physically disabled (laughs). Look, this donation thing has another crucial motive behind it, which is to share... During the exhibition in 2009, many people asked, “why is this collection under house arrest”. This was the word: “house arrest”. To be able to share, to deliver it to broader audiences, especially to make sure it is seen by young people and children is very valuable.

I visit the museum as often as I can and I observe the children and the young people coming to see the collection. The facial impression they have within the very first moment they encounter the collection tells you everything. Children remain frozen. Some get scared, others look at their teachers, yet others cannot take their eyes from the helmet... An indescribable feeling...

Returning to your question, would I donate the amphora collection?

Of course I would, but a collector’s spirit is very different. I cannot live without a collection in my life. Once you start collecting, it seems that your genetic structure changes. You have to keep this spirit alive until the end of your life, for you know you cannot do without it.

What would you recommend to those who would like to build a collection?

First of all, I would recommend collectorship to everyone, for it has a very big role in the development of your character; it allows you to be systematic, calculated, disciplined, curious and forward-thinking. My main advice would be to choose an object they are truly interested in that would contribute to their personal development during the collecting process and that they can enjoy; it does not matter what it is. You can build a collection for everything. You need to choose the object you will like, that will motivate and satisfy you, nourish you, which you can share with others in the future, and which you can integrate into your lifestyle. You benefit a lot from it. I can say that collecting is a kind of therapy. It changes your psychology, your mood; you may see it as a medication able to calm you down at stressful times. It is also very informative; this is why I try to instill this passion for collecting into every child. I failed with my own children, but I still keep trying to do so with others.

I think you have a very inspiring collection. We would not have had the chance to see such a rich patrimony if you had not done what you have done. Although it is not my personal area of interest, it felt mesmerizing when I saw the work, the effort and the knowledge behind it...

Thank you... No small amount of work, indeed. If you could join me in some of my trips and their aftermaths, you would understand better what I went through...

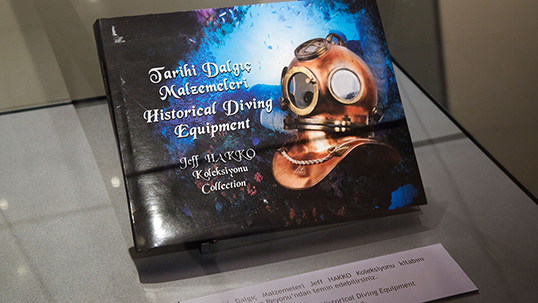

And your collection has a special book as well. Did you prepare it for the exhibition opening?

The book was published in 2009 after the collection was temporarily exhibited at the museum for six months.

I visit the museum as often as I can. I observe the children and the young people coming to see the collection. I see their faces at the very first moment they encounter the collection. This actually tells you everything. There are no words to describe that feeling…

It is a very important publication for those who cannot visit the museum and see t collection as well as for those living abroad...

Each helmet you either see here or in the book weigh around 15-25 kg, and one of them even 45. Then there are the pumps, each weighing 300 kg. It is a very difficult task to transport all these. It took the soldiers and technical officers from the Naval Forces an entire month to plan the collection’s transport from my house to the museum. If the museum did not have the resources, we could not have done it. I told them, “let us make a book together so that the collection is immortalized”. They set up a studio at my house and each object was photographed in detail. The book is currently available at the museum store to those visiting the exhibition. Moreover, the books received plenty of attention abroad. Its fourth edition will be out in the days to come.

This interview is conducted by Emel Erden on behalf of Art50.net for TEB Private.

UP

UP