1 / 33

1 / 33

1 / 33

1 / 33

As the curator of Istanbul Photography Museum, one of the first of its kind in Turkey, Cengiz Kahraman has gradually and professionally developed his passion for photography after a degree in art history in addition to his experience in publishing. He is an important figure who currently reflects his academic background and meticulous working style in his publications and exhibitions, managing to view the act of collecting from multiple angles. We had an intense conversation with him regarding his interdisciplinary approach to collecting photography, the museum and his other projects, rich in tips and guidelines for the photography enthusiasts.

You graduated from Mimar Sinan University Department of Art History. Then you worked as a photography editor in various publications, as a photography consultant, museum curator, etc. How, when and where did your paths cross with photography?

Our paths crossed with photography in 1994, while I was working on the Istanbul Encyclopedia composed of eight volumes, in collaboration with the History Foundation and the Ministry of Culture. In other words, it happened twenty-two years ago. There I met people who were interested and knowledgeable in photography. During our collaboration I became informed about photography’s areas of use and I realized how valuable it was to archive and collect it.

As collectorship is perceived as something they occasionally look at or show to their acquaintances by the collectors here whose main objective is to accumulate, their knowledge, ideas and techniques of reading photographs remain insufficient. This is why, as I kept collecting photographs, I realized that identity information, the photographers, their motivations, chronologies and locations are very important.

The following problem exists in Turkey; if you are working in this field, it is not that easy to find the people or the institutions that might be of help to you. The newspaper archives go back only to a certain point in time and you cannot reach them properly either. This is why I began to collect documents such as photographs, postcards and photo cards related to my area of study, and this had the natural consequence of introducing me to the second-hand book sellers. This is how it began. But of course this is a very comprehensive area and every new thing teaches you something else. Then I slowly began to discover photographers. As collectorship is perceived as something they occasionally look at or show to their acquaintances by the collectors here whose main objective is to accumulate, their knowledge, ideas and techniques of reading photographs remain insufficient. This is why, as I kept collecting photographs, I realized that identity information, the photographers, their motivations, chronologies and locations are very important. So without all these, collectorship is only an act of accumulation.

How did you become interested in collectorship?

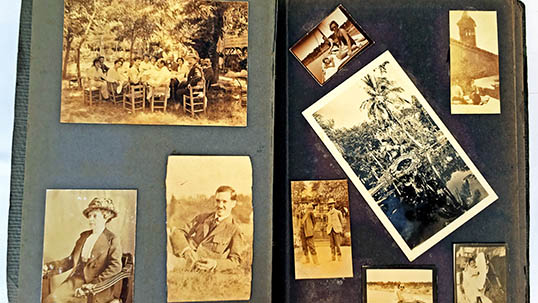

Actually for me, such things, including working for the Istanbul Encyclopedia, happened coincidentally. The History Association was also publishing the Istanbul Magazine, its first publication. Consequently, my relationship to the magazine developed naturally. Then the History Magazine followed as a third publication and I began to work as the photography editor of all the three publications. So consequently you remain face-to-face with a multilayered field. One is a magazine about urban culture while the other is about history, and the third is a scientific publication talking both about the past and the present. Later I edited photographs for the Turkish Encyclopedia of Trade Unions. I also had the chance to work on some of the foundation’s exhibitions taking place back then. So I had the opportunity to meet many people and to see many photographs. But for me, the main reason why I became interested in this venture I am in the twenty-third year of was my encounter with an album in the earlier days of my career. It was so interesting. It belonged to Iraida Barry, a Russian lady and sculptor who came to Istanbul. A very beautiful and attractive lady. She married Albert Barry, who had been living in Moda for many years and who was a dentist like his father. The Barry family was very affluent and they deeply enjoyed taking photographs and genuinely interested in it as amateurs. I have been working on this subject for many years now, and in time, a corpus emerged with a growing number of photographs, information, diaries, journals and letters. So the first photographs I acquired came from such an album belonging to Iraida Barry. It contained numerous amateur but very successfully taken photographs of Istanbul. Perhaps this was one of the things that changed my life. This encounter happened twenty-three years ago and I still reach other fragmented parts of that story. For instance in recent years I found out that part of Iraida’s collection was at the Columbia University in the USA. This is such a big story and there are thousands of images about Istanbul. The majority of them have never seen the sunlight, and they encompass a period from early 1900s to 1960s. What I understand and what is evident is that they took pictures with a great awareness and they had an aesthetic approach although they were not professionals. Once I will prepare an exhibition and a book about this story, these images will be shown for the first time even though they were not meant to be.

What does the ”Spirit of Collectorship” mean to you?

For me, collecting photography means to share and to create things related to it. As children we all collected things such as marble balls or chewing gum cards, and this was only to say to the others that you had the better ones. But the next step of collectorship is to turn that collection into a creation and to share it. I personally observed that some collectors hesitated to share with others the material they had. Such collectors may surely have the following state of mind as well; they work on a certain subject for years and they themselves dream about doing something with it, wanting to be the first to use the material they have. They don’t share it with someone else and these dream projects are generally never realized. It is crucial for me to share the documents in my collection through books and exhibitions. Some collectors do it just for the sake of accumulating things. But it is also very important to classify them, for an average painting collector, for instance, can acquire up to five-six hundred works and the works can be well known as well as very valuable. But when it comes to photography and similar things the number goes up much more. You may have thousands or even tens of thousands of images in your hand and the collector may begin to forget them, not finding them and thus the document remains out of circulation. With well-organized post-collecting work I began to transfer the images to the digital environment. This way, as you learn new things you have a better chance to share it with others and you are able to see the big picture in what you want to do. And projects gradually emerge out of it.

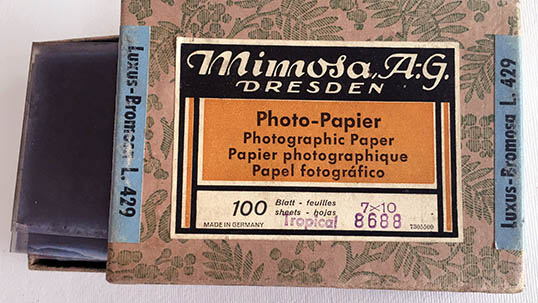

In my collection there are probably around three hundred thousand photographs in different sizes. Don’t think of all of them as single prints; some of the things I value the most are the negatives of glass and plastic. It is already a miracle that these managed to survive, for it is very problematic to preserve them and to keep them clean.

Can you inform us about your collection’s content? What are the recurring themes and dominant subject areas?

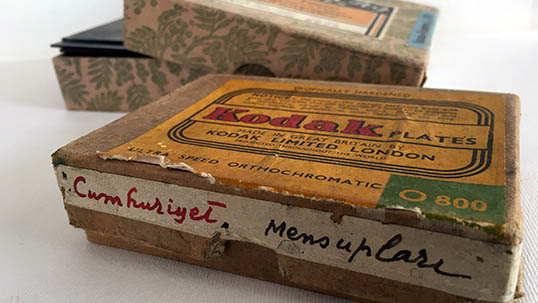

Lately I have been interested in photographers for quite a while. Next year I want to organize an exhibition and make a book about Namık Görgüç, a press photographer that I find very important. He worked at Cumhuriyet newspaper since the day it was founded in 1924, where he created the photography department and the dark room. Due to his untimely death in 1947, he is not sufficiently well known. Additionally there are very important photographers I am interested in and whom I have been examining for quite a while. I think press photography is, in this sense, an area in its own right. The works were poorly preserved, dispersed, even absent from their own archives and can only be encountered in an auction context. I try to bring these back together. There are also thematic lines; my main subject area is Istanbul. I have also been working on social life and entertainment for a long time. There are important names in portrait photography and I need to bring them together and work on the photographers’ identities. For example, Ferid İbrahim Bey, Turkey’s first photojournalist deserves to be studied. Later he acquired the surname “Özgürar”. We contacted his family and grandchildren but in Turkey it is complicated to work on such things and publications. They have to be done meticulously.

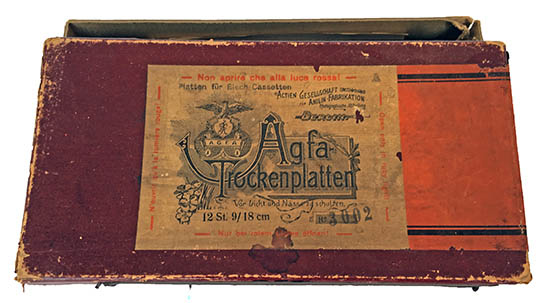

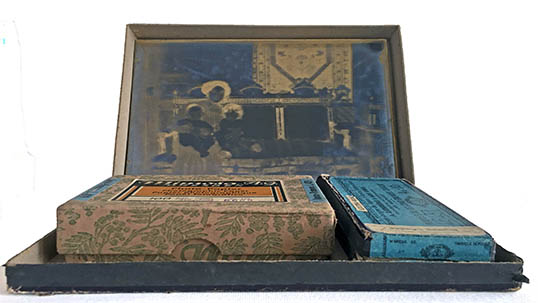

In my collection there are probably around three hundred thousand photographs in different sizes. Don’t think of all of them as single prints; some of the things I value the most are the negatives of glass and plastic. It is already a miracle that these managed to survive, for it is very problematic to preserve them and to keep them clean. As most collectors value the printed photographs of their era they do not show much interest in negatives. For me it is crucial to collect them and to digitalize them. Even in this exhibition there are photographs printed from old negatives. I can say that I have a good collection of glass and plastic negatives.

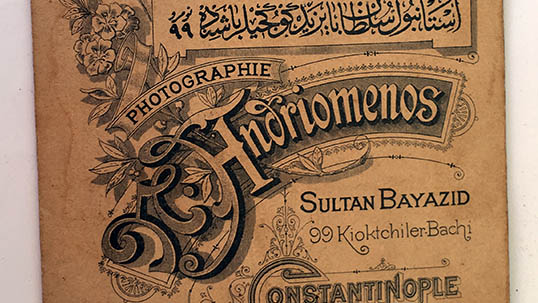

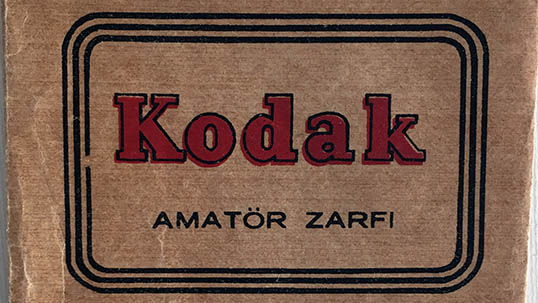

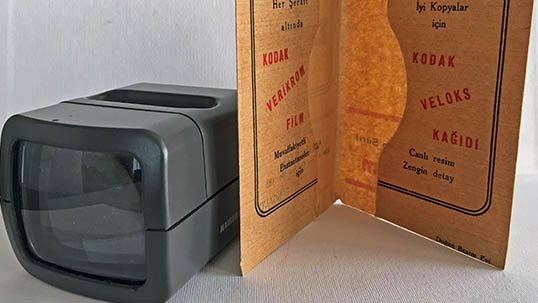

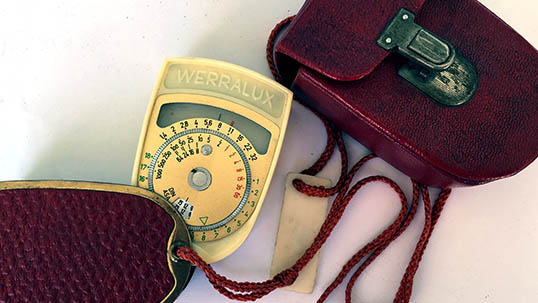

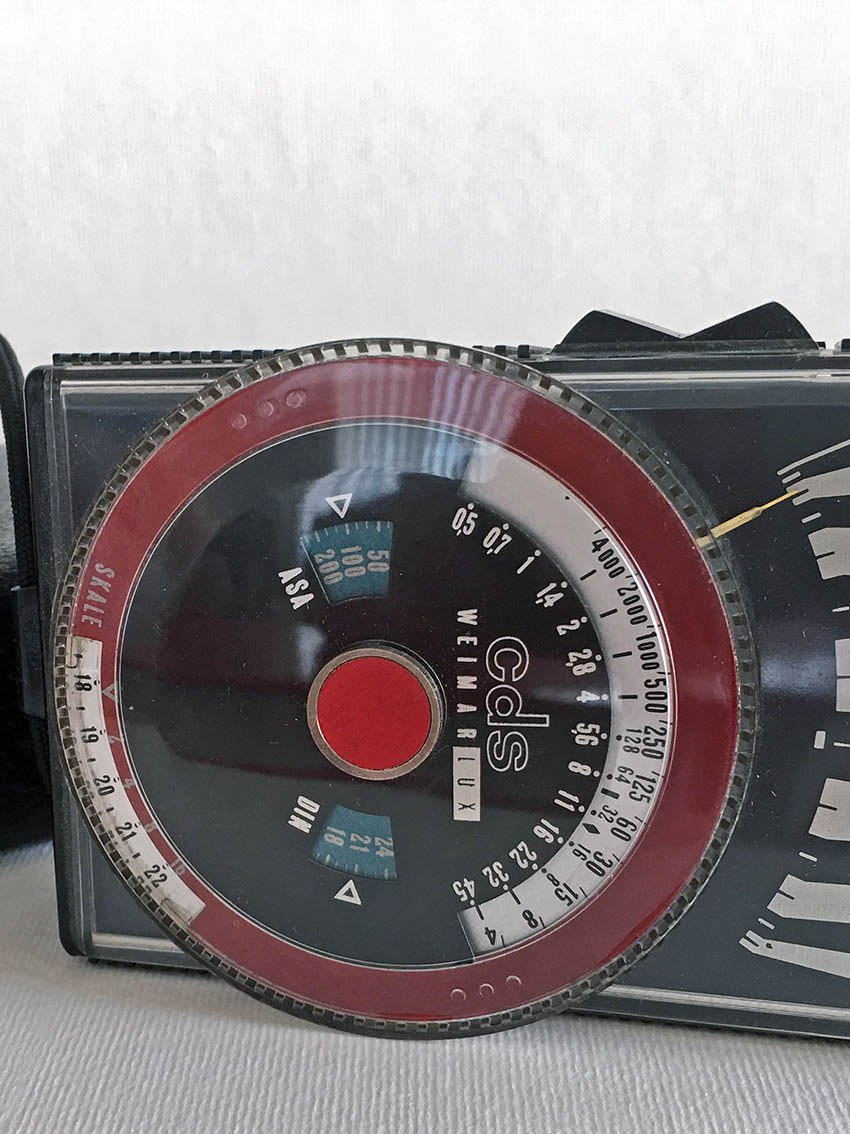

There are photography collections featuring cameras and dark room equipment but they remain outside my scope. As my work is about exhibition and publication I focus on the photograph; the other materials are more static. There are also things like the ephemera, containers with the photographer’s identity information on them, advertisements and cardholders that are no more produced and that were thrown away as worthless objects while the photographers were still alive. If someone kept these things their enthusiasts manage to reach them. For example we probably haven’t kept an analog film box, probably because we felt like it would continue to be produced forever.

How did you develop your collection? What would you say about the photograph’s acquisition and preservation?

It was initially cheaper to buy photographs, postcards, ephemera and photo cards; as their enthusiasts grew in number and the supply decreased, it became a more expensive venture.

In addition to all the big auctions there are also the weekly ones. I used to find the second-hand shopkeepers very useful and they informed me as well, calling you about the newly arrived items that could be of interest to you. Friendships built in time also help you to share and support you.

Something always makes people curious: how do so many photographs and especially family albums end up in second-hand shops? Photographs never leave a household on their own. They leave with many other antiques, furniture and books to be sold that belong to that household. Antique buyers forward these photographs and books to the second-hand shopkeepers they know. So there is some sharing going on. Interestingly, there are also items thrown in the garbage or given away to the junkmen. I suppose many other things had previously ended up in the garbage for they had been considered financially worthless. There are also collectors who decide to dissolve their years-old collections. Some collections are given to auctions or shopkeepers, sold or donated by beneficiaries. Sometimes another person takes over and prepares a project out of these collections that were built in many years but that never became a subject of study.

What are the main guidelines for collecting photography? How did your researcher profile contribute to your collectorship? Are there any specific criteria?

I would like to emphasize that, particularly after a certain date, you must be careful about copyright issues. Those who will start collecting after a certain date must have information about the photographer’s identity. They have to check if the photographer gave permission for multiple editions. You might like Ara Güler’s works, there is no problem in hanging an image you bought in your home but if you hang it in your hotel they might sue you for copyright infringement and they might ask if it has a certificate of authenticity in case you wish to sell it in the future. But the period prior to 1950 is considered anonymous. For instance, as I mentioned earlier, I couldn’t reach his family even though I conducted a long-term research on Namık Görgüç. A publication without his family’s permission may become a legal problem in the future. These rights remain unreserved in 2017, on the seventieth anniversary of his passing, so I will be able to realize the project. In this field I have seen that it is not easy for someone to firmly say that they took a certain photograph. Photographers may exchange images; especially press photographers buy each other’s archives. You see their signature on images they cannot have produced at that time. Moreover, many people who do have little information add the author’s name underneath the image and the incorrect information keeps being reproduced. The best example for it could be Selahattin Giz, the photojournalist. Most of the images from the 1930s are indexed with his name as author. But in my research I have seen that he himself is an archivist and collects photographs from his friends. He stamps them in the back as “Selahattin Giz Collection-Archive” but then the incorrect information is processed. As a result, the incorrect replaces the correct after several repetitions, and it doesn’t make a difference if you say it is incorrect. There is also another thing in Turkey, when you say photography Ara Güler’s name comes to mind. Ara Güler is a great photographer but it is often perceived as if taking pictures began in Turkey with him. However, Pictures were taken in Turkey since 1840s. I am also very curious about this; numerous exhibitions and books were made for Ara Güler. There is also his contemporary, Ozan Sağdıç, currently eighty years old. He is also a great photographer but his work was not sufficiently exhibited or published. These need to be done, absolutely.

We know that the painting market in Turkey became dynamic in the last four decades. As far as I heard from the experts in the field, in 1970s you could buy certain paintings at very favorable prices and make a very profitable investment. I think photography will have a growing importance as an investment tool and will have a considerable market in the future.

What are your thoughts about collecting photography and “new media” in Turkey, areas that, until recently, collectors were hesitant about?

We know that the painting market in Turkey became dynamic in the last four decades. As far as I heard from the experts in the field, in 1970s you could buy certain paintings at very favorable prices and make a very profitable investment. I think photography will have a growing importance as an investment tool and will have a considerable market in the future. As contributing factors, Leica is opening a new gallery and Doğuş Holding aims at building this museum about Ara Güler. As photography is taken by everyone, the number of its enthusiasts will grow and it is not something difficult to sell like painting. For painting you might want to spend big sums, make investments via timely acquisitions via expertise but there is risk involved in all of this. In collecting photography, on the other hand, you might begin with a modest budget. I know people who regularly buy with a portion of their monthly wage. What matters is to be careful about legal permissions, certificates and edition numbers when buying contemporary photographers’ works.

While you pay a certain sum for a work with five editions, you pay less for one with two hundred editions. This is a newly emerging market, after all. On the other hand, the collector might buy the work from the galleries or the exhibitions, but when auctions are concerned, the work’s “uniqueness” is very valuable. It might be an anonymous work with no author that you might never come across again, printed at its time of production and perhaps a unique copy. Moreover, the developing field of photography publications also creates its own area of collectorship. A book printed in a thousand copies might never be published again. If you did not acquire certain books at a time you might never find them now.

Your thoughts about photography collectorship in Turkey? And your prospects for the future?

The photographers I mentioned earlier have already started to build archives and collections and they most probably continued doing so as they regarded it as part of their work. For example Selahattin Giz and Faik Şenol acquired other photographers’ works as well. We may also talk about some institutions. For example German Archaeological Institute acquired and preserved part of the Sebah & Joaillier archive of glass negatives, an important photography workshop of its era. Another important institutional collection, Abdülhamid II’s Yıldız Albums, is currently based at Istanbul University Library of Rare Works. Only one percent of it has been published but there is such a great treasure there, still in the process of being digitalized. I can also mention the Istanbul Research Institute, Salt Galata, City University, Atatürk Library, Yapı Kredi Bank Selahattin Giz Archive. But of course these were recently created collections, in 1940s there was no such thing. Then there are some figures who collect systematically, Herman Boyacıoğlu is the first that comes to my mind. But his untimely death did not allow him to do something with his collection.

Ömer Koç is one of the most important collectors of our time. He has a good photography collection and his art consultant Bahattin Öztuncay published great books and organized great exhibitions out of a portion of this collection. If what you collect does not reach the public via a publication, it remains idle.

Editing photography, research, curatorial work and collectorship… You have a very wide range of working fields. How do these fields support each other?

It has been a great opportunity for me to curate the Istanbul Photography Museum. Thanks to it I met a much larger community of photographers and photography professionals, doing exhibitions. In terms of publishing this is a great advantage, for you write something about a subject or a person, and surprises may come about. Someone that worked in that subject area might find you. At these points in which you become more visible some people might approach you to sell their collections for this sort of material always tries to find its buyer. I have friends from among second-hand shopkeepers with a well-developed ethical position. They want to sell things to those who are more inclined to do a better work on them, not to an unethical person with a better offer. So if no one knows you are collecting, if you only collect things and look at them at your house all by yourself, this would later become a kind of an obsession. It is already an obsessive endeavor but rendering your collection visible again is a great pleasure.

For me, the following was at the very beginning of this professional story; I was responsible for finding photographs suitable for what people wrote. After going on like this for a long time, I realized every image had another story, so I figured out that, instead of finding images for texts, I had to write texts for the images that I had.

Important projects including exhibitions and publications you have realized so far?

For me, the following was at the very beginning of this professional story; I was responsible for finding photographs suitable for what people wrote. After going on like this for a long time, I realized every image had another story, so I figured out that, instead of finding images for texts, I had to write texts for the images that I had. This is how I made my book “Istanbul Winter Diary 1929 and 1954” published by Yapı Kredi. I had to write real stories for these images related to these dates, so I went on to work in newspaper and magazine archives of that time. I discovered some images were published in these media, so I found their stories as well. In my book there is a very important chapter on the Kurtuluş fire. I had many images of fire in my collection but I was not able to determine exactly where they were taken. During my research in newspaper archives I found out they belonged to this event. The story in the images published in a 1929 newspaper showed me once more that every photograph had a story. In those years, archive images were published again and again depending on the daily needs. So they did not see a problem in using the photograph of a snowy winter from years ago during other rough winters. Again, as it is considered as a filling material complementing a text, our images seldom have captions. In this book I also wanted to show how important this was. When you conduct research about the identity of an image and its producer you learn other things as well. It is actually a kind of puzzle, like solving a riddle. So it is also fun. We organized exhibitions at Istanbul Photography Museum and Caddebostan Cultural Center for some of the photographs in this book.

Can you tell us more about the Istanbul Photography Museum?

It was founded in 2011 by Fatih Municipality and the Friends of Photography Association. It has four galleries. The association founded with Gültekin Çizgen’s initiative, on the other hand, has Selim Seval and Serhat Gökçaylar in its board. Since 2013 I have been working as the museum’s curator and director. In addition to the permanent collection, in our program we also have temporary exhibitions from different fields, with important Turkish and international photographers. Our previous exhibitions include “From Press Photographers I”, “Us, Photojournalists, Used to Feel So Cold”, Güngör Özsoy’s “Yeşilçam”, Ozan Sağdıç’s “Photography’s Poet”, Ersin Alok’s “Retrospective”, Ali Borovalı’s “Ice”, Abdurrahman Antakyalı’s “Child Boxers”, Kemal Baysal’s “Colorful Istanbul”, Tomek Sikora’s “Chopin”, Stefane Herbert’s “Imaginals”, Hans-Jürgen Raabe’s “990 Faces”, Şemsi Güner’s “Retrospective”, Serkant Hekimci’s “Railway Stories”.

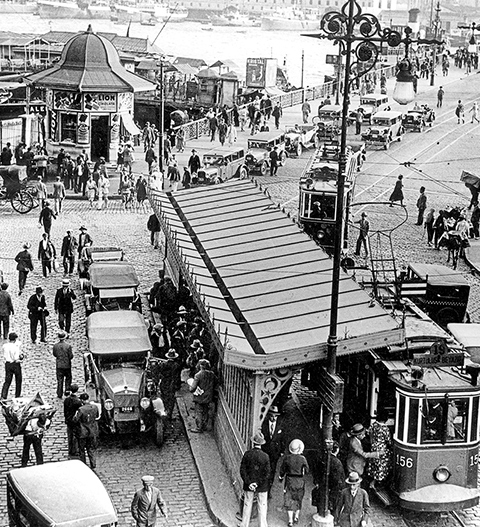

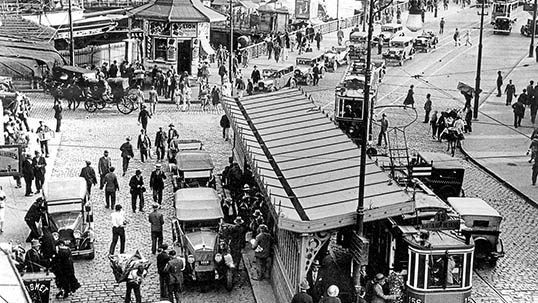

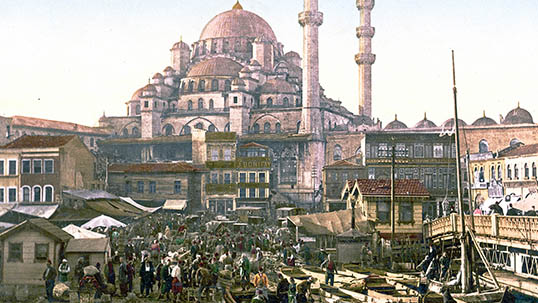

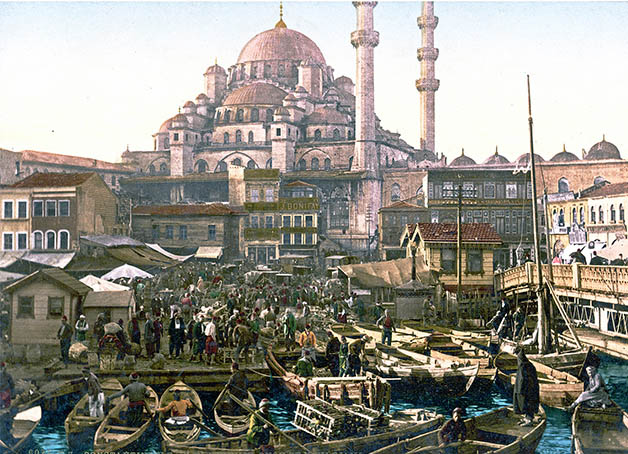

The current exhibition that I have curated, “Historical Photographs from the Historical Peninsula I” features images from my own collection. With daily life photographs from various years taken in the “Suriçi” area of Istanbul, it presents human stories. The other galleries in the museum host the exhibitions “Olympics” by Murat Sezer, “NBA Thrill” by Tolga Adanalı and “Soccer Instantes” by Emre Oktay respectively.

Collectors must first consider the following: those photographs you buy and put in your library or your desk drawer belong to all of us. They shall not think that, once they own them, they own all the rights. So they belong to the public and they just happen to end up in the collector’s hands. So they need to be shared as much as possible.

In your opinion, what kind of a void does this museum fill in Turkey in terms of photography?

The museum is an attraction for photographers as much as it is for visitors. An area where they can share with the photography community all the work they produced over the years. The museum has a lot of foreign visitors during the summers. Thus we share our photography culture with them. Even though many people love taking pictures with their mobile phones, they are not followers of photography. The museum and its rich exhibition program contribute to the emergence of a wider audience.

What would be your recommendations to those interested in collecting photography?

Collectors must first consider the following: those photographs you buy and put in your library or your desk drawer belong to all of us. They shall not think that, once they own them, they own all the rights. So they belong to the public and they just happen to end up in the collector’s hands. So they need to be shared as much as possible. They shall try to make publications or collaborate with those who can. They can determine a budget and follow the auctions accordingly. They can find more affordable works on the Internet, especially on international websites. The main criterion is not the unit price; the larger work is not necessarily the more expensive, smaller works can also be very valuable. They should also digitalize all the works they now buy with ease. The classification possibilities have immensely developed and they allow you to use the collection effectively. If you cannot find an item in your collection, it doesn’t belong to you! Thus they need to dedicate time to the item they buy and work on it. I have also witnessed years-old collections being dispersed without being used, so institutionalization is vital. The most pleasant part of this venture lies in the beauty of finding things thanks to coincidences and discovering them later on. For instance, as you browse numerous photographs in an auction, you notice something in an image that no one else did, you figure out it corresponds to something personal in you and it becomes valuable for you. Such coincidences related to discoveries give you a lot of pleasure.

This interview is conducted by Ali Gazi on behalf of Art50.net for TEB Private.

UP

UP